THE Canberra was lost against the gloomy backdrop of a drizzly Southampton day. Alongside, several hundred screaming people – wives, parents, girlfriends and children – grouped at the dockside to wave goodbye as the patriotic sounds of Land of Hope and Glory and Ride of the Valkyries conspired to induce shivers.

Two young women wore T-shirts reading “Give the Argies some bargy” – a message of encouragement not just seen by the soldiers embarking but by a curious world watching on the TV.

And then perhaps the most poignant imagery of all: as the slate grey waters parted, the TV lights pierced the evening darkness to illuminate placards hanging from “The Great White Whale”.

The great hull of the Canberra, the pride of the P&O fleet, was draped in sheets bearing moving farewell messages.

It was April 9, 1982, a Good Friday of cold and drizzle, and the marines and paratroopers were on their way to re-claim the Falkland Islands after the Argentine invasion.

Most watching at dockside and in homes across Britain had never expected to see an English war in their lifetime.

Three days earlier, elements of a battleship “Task Force” had also left Portsmouth.

Leading the way were two aircraft carriers, HMS Hermes (the flagship) and HMS Invincible, the assault ship HMS Fearless, plus other landing ships and their accompanying escorts.

They, in turn, had been preceded by warships which had been carrying out manoeuvres off Gibraltar plus three nuclear-powered submarines.

But Canberra, manned by a volunteer civilian crew of 400, was the key facilitator: she carried 2,400 first wave invasion troops within the warren of decks and cabins that had been hastily converted for troop movement just two days after returning from a world cruise.

The liner’s next five cruises had now been cancelled – ruining 3,000 holiday plans in the process – and machine guns adorned her deck rails. A helicopter flight deck had also been built by Vosper Thornycroft’s shipbuilders in Woolston.

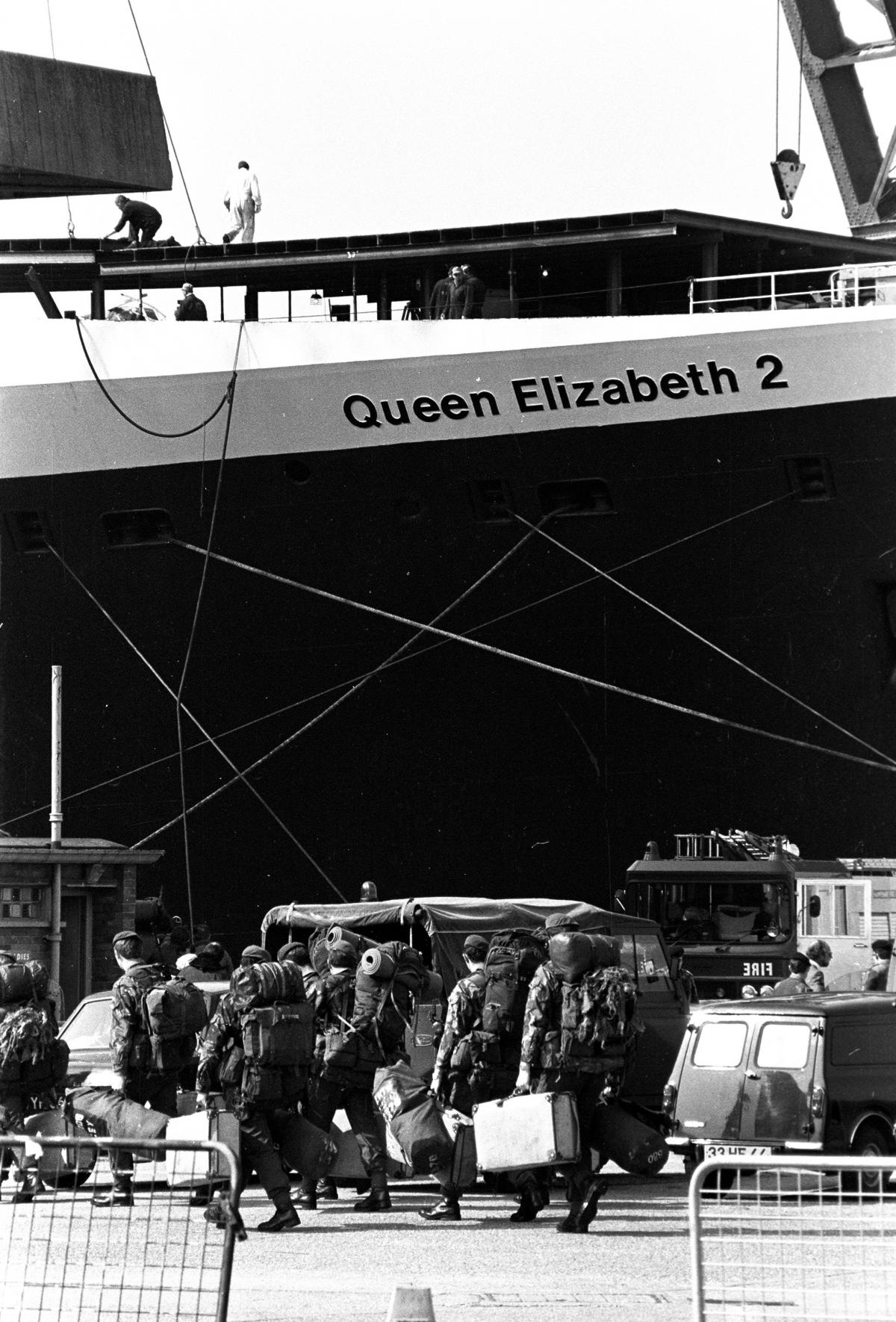

The most famous liner in the world, the luxurious QE2, would soon be called upon to do her duty too, just as Queen Elizabeth had done during the Second World War.

Southampton’s input did not stop there either.

Royal Fleet Auxiliary ships sailed from their Marchwood base, including Sir Galahad and her sister ship, Sir Tristram. Both were specialised vessels with bow and stern doors allowing roll-on roll-off capability. Designed as multi-purpose troop and heavy vehicle carriers, they could beach and unload tanks directly onto the shore through their bow doors.

In all, more than 110 ships and 28,000 men headed for the South Atlantic to reclaim the Falkland Islands.

Yet, for a watching nation, it was the emotional departure of Canberra that murky April day that finally brought home that something big was happening.

Canberra was soon out of view and beginning her 11 day journey to Ascension Island, a volcanic plug of land in the middle of the Atlantic wilderness. Here the British Task Force would rendezvous before heading the 4,000 miles south to the wintry Falklands. At the fleet’s heart would be the gigantic Canberra, accompanied by her escort HMS Ardent but nonetheless very visible and very vulnerable.

How many would die at the bottom of the world? And where were the Falkland Islands anyway?

On May 12, the virtually defenceless ‘Great White Whale’ entered the exclusion zone, accompanied by its protector, the escort frigate HMS Ardent.

That same day, 8,000 miles away in Southampton, the most famous liner in the world prepared to join her.

A little girl watched intently as the heavily armed men, laden with mortars and anti-tank weapons, filed down the gangways and into the lower decks of the British merchant fleet’s flagship

As the first of 3,000 men entered QE2, the youngster turned to her mum and asked: “When will daddy be back?”

It was a question no one could answer.

From first light on May 12, the troops of 5 Infantry Brigade had begun streaming into Southampton to join the Cunard liner which had been converted into a no-frills troopship, an instrument of war, in just one week thanks to shipyard workers in the Eastern Docks.

Out went the luxury fittings which were replaced with boards to protect the plush carpets from heavy army boots. And out went the pate foie gras, smoked salmon and other delicacies in preference to 18,000 cases of beer, 12 tons of chips and 100 tons of meat.

Meanwhile, work continued on the ship’s three new helicopter pads.

As with Canberra, the pads were built at Vosper Thornycroft’s Woolston shipbuilding yard where 250 men worked around the clock.

Now QE2 was ready with the second wave of ground troops.

Aboard were the Welsh and Scots Guards and the Ghurkhas, the tough elite from Nepal whose motto was: “It is better to die than be a coward.”

That same day, 8,000 miles away in Southampton, the most famous liner in the world prepared to join her.

A little girl watched intently as the heavily armed men, laden with mortars and anti-tank weapons, filed down the gangways and into the lower decks of the British merchant fleet’s flagship

These men, based at Church Crookham in Hampshire, could scramble 1,500 feet up hills in under 15 minutes and had packed their traditional kukris knives with their modern-day armaments.

They joined members of the Royal Artillery, Royal Signals and Army Air Corps who made up the 5 Infantry Brigade, a quick reaction force.

To the strains of Auld Lang Syne, the great liner moved off, a forest of frantic hands and flags bidding farewell.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article