AS WE enter the early stages of the period when all clocks and watches have been put back one hour to return to normal time, so we head for the 105th anniversary of the Daylight Saving Scheme, which began in 1916.

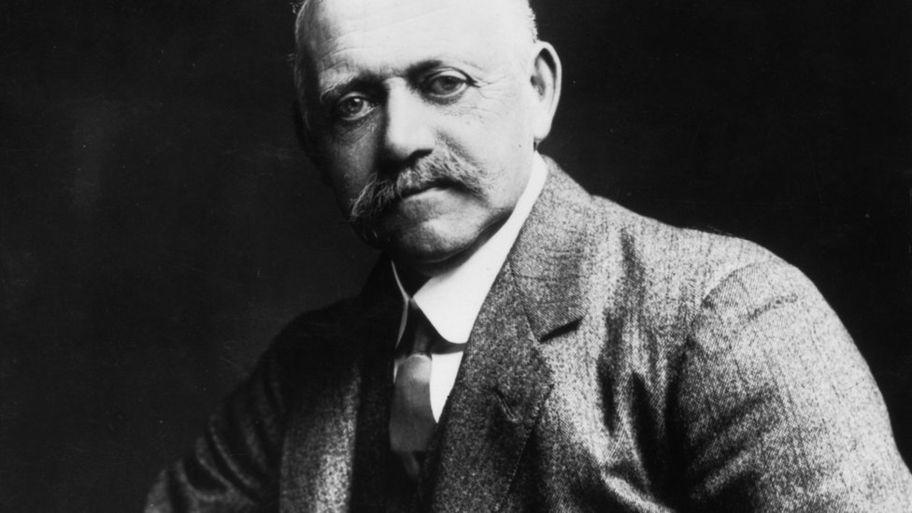

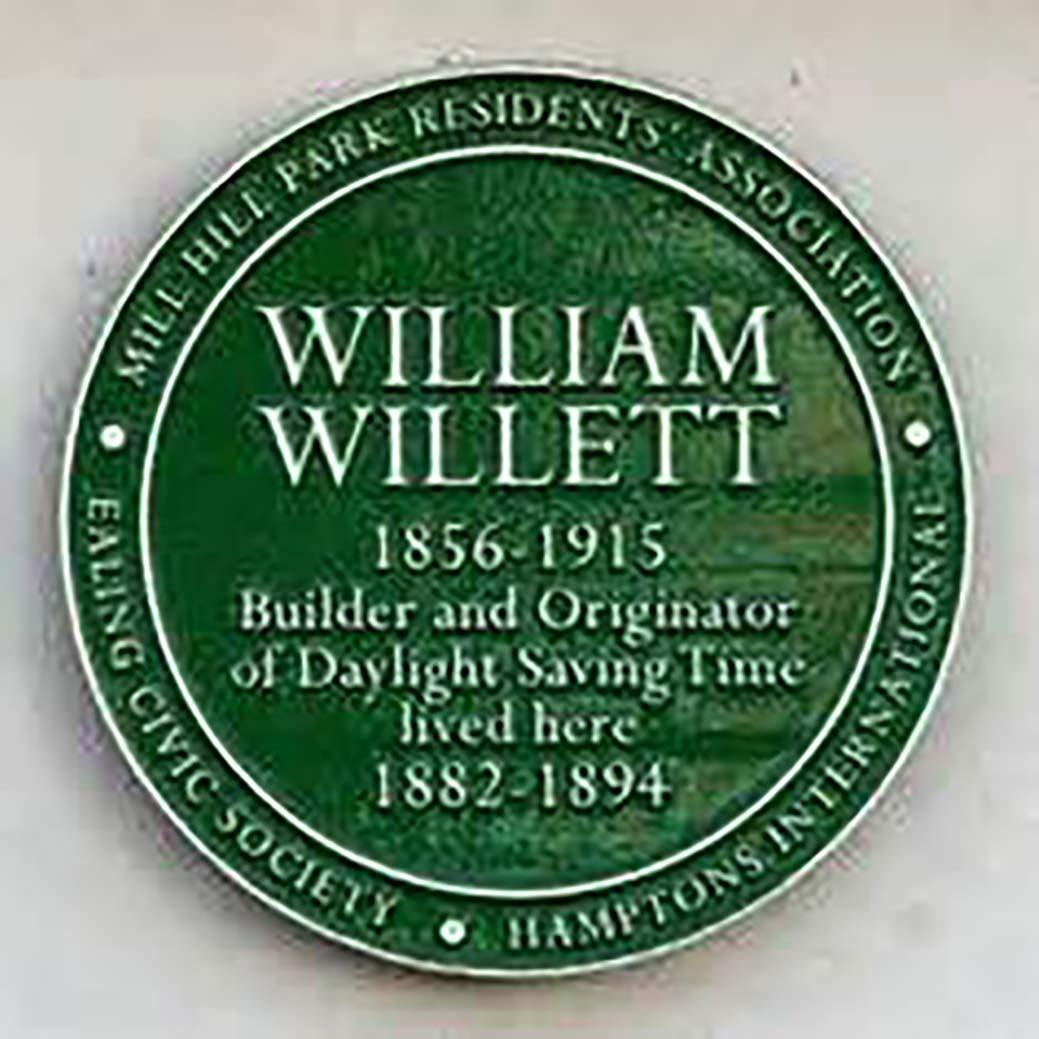

Although Benjamin Franklin, the American statesman and scientist (1706-90), first thought of the idea to make fuller use of the hours of daylight by advancing the time, its introduction was due to a campaign by William Willett, who lived in Chelsea, and was a designer of large houses.

As a builder he was well aware of how the dark evenings in the summer prevented him from completing certain jobs, and in 1907 it occurred to him that most people woke up an hour or two too late in the summer months and they had a short evening for outdoor

recreation.

For the next eight years, William Willett devoted himself to proving to members of Parliament how the advancement of time in the summer would benefit the country.

He succeeded in getting Robert Pearce, a Member of Parliament, to introduce a bill in the House of Commons that “would save fuel for lighting and heating”.

When the first mention was made in the newspapers, the general public scoffed at the idea, and it would never have been tried if the First World War had not broken out in 1914, with the necessity for economising artificial light, which in those days was mainly provided by gas.

The introduction of electricity was only just beginning, but in the following years this new form of lighting and heating was to change the whole world.

Unfortunately, Mr Willett never saw his idea come to fruition as he died on March 4, 1915, aged 59, in Chislehurst, Kent, just one year before the Summer Time Act became law, in May 1916.

A memorial was later set up in Pett’s Wood, on the south-eastern outskirts of London, in memory of William Willett.

On August 7, 1925, the Daylight Saving Act was made permanent. It was fixed that “summer-time” would begin at 2am on the third Sunday of April and end at 2am on the first Sunday in October every year.

The act applied to Great Britain, Northern Ireland, the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man, but later on, other countries copied the idea.

Various extensions were made to the times over the following years, including the Second World War, and in the 1960s, while Double Summer Time (two hours in advance) was put into force during 1941-45, and 1947 (the year of the Great Freeze-up), to save fuel.

In the early years of the scheme, objections were made by various organisations and professions, including farmers, who argued that because farmwork usually began at sunrise, it was impossible for them to gain anything by moving their clocks forward.

Of the many farmers in the Basingstoke area, Joseph Kimber, at Viables Farm, stated that he found it difficult to adjust to the twice-yearly change of time to milk his cows, and the others said likewise. But they got used to it after a while.

Meanwhile, at the Basingstoke Electricity Works in Brook Street, which was built only two years before the 1916 Act of Parliament came into power, George Broadhurst, the electrical engineer, who was in charge of making sure that the town was getting a true amount of electricity, realised that the autumn change of time could cause a power surge in places.

At that time his responsibilities were for the street lamps and a few shops, offices and factories. It was to be another five years before homes were fitted with wiring to light and heat the many houses in the town, in 1921.

Tom Pritchard, the town hall keeper, in Basingstoke Market Place, had to make the long, steep climb up a circular metal staircase into the clock tower to change the hour hand when the law came into progress in 1916.

He already spent some time winding up the clock mechanism to keep it working each week, but to make sure that all four faces were right was a hard task twice a year, as it was all done by hand.

At the two railway stations in Basingstoke, the station masters, Albert Kneller of the South Western, and Henry Giles of the Great Western, had to be careful that their passengers were aware of the times of the trains arriving at the station while adjusting their clocks in those first years of the scheme.

Everybody was affected by the changes to the clocks. In the following years, people became used to the annual task of putting the clocks forward and back.

Some folk even enjoyed telling shopkeepers and other businesses that “You haven’t put your clock right” when the owners had not adjusted them during the first day. And they still enjoy telling them now!

This column has been updated and was originally published in The Gazette on November 10, 2005. It was written by the late Robert Brown, a former photographer, columnist and historian at The Gazette. He wrote eight books on the town’s history and sadly passed away on March 25, 2019.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel