An Anglo-Saxon girl's skull found in Basingstoke with her nose and lips cut off is the first known evidence of punishment for female adultery, archaeologists have said.

The cranium was unearthed in Oakridge where Mullins Close stands today, during a dig in the 1960s.

It was discovered before the historical area was developed for housing.

The skull had been in storage until recently when experts at the University College London’s Institute of Archaeology carried out analysis.

Their research found that that girl, thought to have been between 15 and 18 at the time of her death, had her nose and upper lip cut off in what experts believe was a ritual punishment for adultery.

She suffered a "cut through her nose that went so deep it cut through the surrounding bone".

Their research found she may have also been scalped as part of her punishment.

The team of researchers from University College London (UCL) believe she died shortly after suffering the injuries, as the remains showed no evidence of healing.

Using radiocarbon dating, the researchers were able to estimate that the remains date back to between 776 and 899 AD. Despite the fact her skull was found in Oakridge, they don't believe she was local to the area.

"This case appears to be the first archaeological example of this particularly brutal form of facial disfigurement known from Anglo-Saxon England," the UCL team said in a press release for the findings, published in the journal Antiquity.

The case predates all previously known historical records of such punishments by almost a century, the study said, and it is the first physical evidence to support what written records had shown.

Law codes from the Anglo-Saxon period - which lasted from the Romans' withdrawal from Britain in 410 AD to the Norman Conquest in 1066 - show that punishments like these were served out to adulteresses and to slaves caught stealing.

The team of archaeologists and scientists led by UCL’s Garrard Cole found her wounds showed no sign of healing.

Their report was published in the journal Antiquity on earlier this month.

Oakridge's rich history

The skull in Oakridge cranium was found close to the boundary between part of the parish of Basing in the Hundred and the estate of Chineham during the 1960s.

Both were significant places in their own right, with a royal manor being constructed in Basing by the 10th Century.

Oakridge may have become a boundary between these locations because it was the site of an Iron Age settlement, whose earthworks may have still been visible in the Anglo-Saxon period.

Researchers said this may have helped define local borders as Oakridge is located on the western boundary of the Anglo-Saxon estate of Chineham (highlighted in light grey) in Basingstoke Hundred.

Discovery of the skull

The Oakridge cranium was discovered accidentally during a rescue excavation at the site in the 1960s. Prior to the construction of a housing estate on the site, archaeologists were permitted to conduct limited recording and partial recovery of finds.

This revealed evidence of an Iron Age settlement, whose earthworks may have been why Oakridge became an Anglo-Saxon border.

A well and Romano-British burial were also discovered and catalogued. The mutilated cranium was found by accident in the spoil heap produced during excavation of the Roman burial.

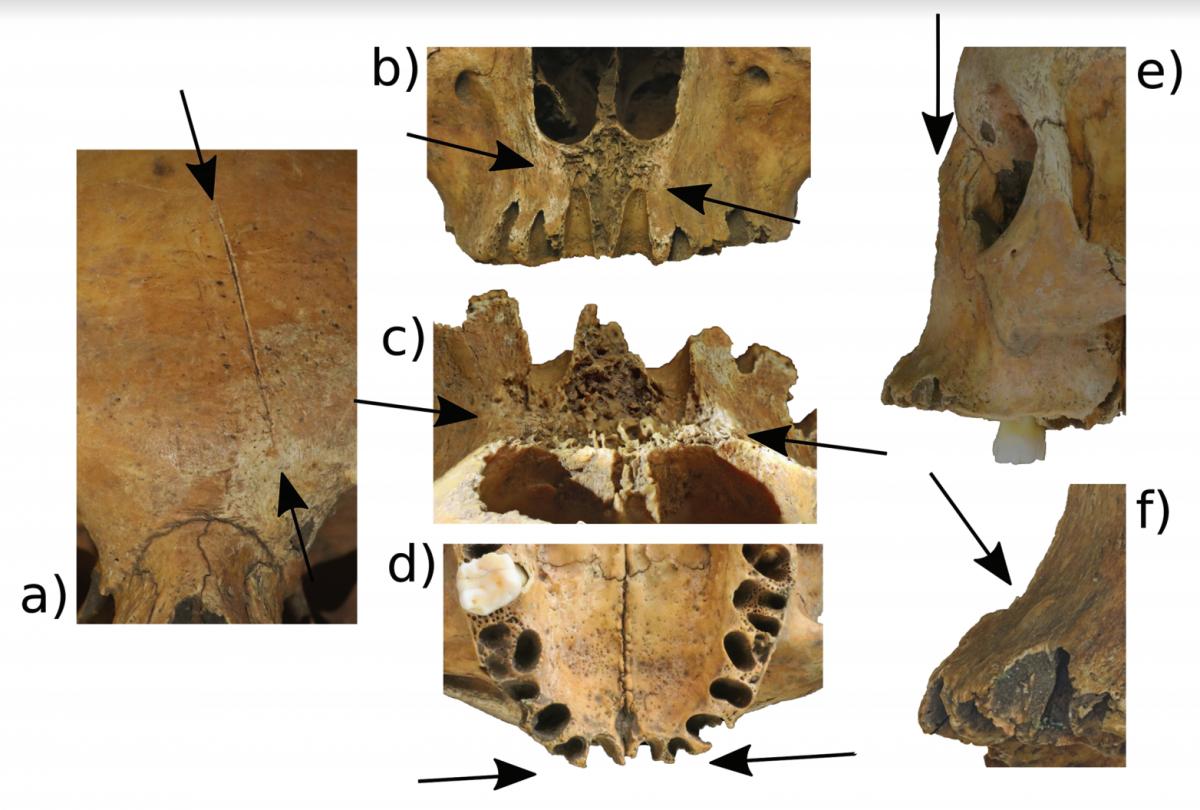

The cranium Decades after its discovery, this cranium has finally been fully analysed. The researchers identified it likely belong to a young woman, aged 15-18. They suffered from several facial injuries around the time of death.

This included a cut through the nose, so deep it sliced through the surrounding bone, and another cut across her mouth.

There was also a cut across her forehead that may represent an attempted scalping, or perhaps an aggressive attempt at cutting off her hair.

They also carried out radiocarbon dating, revealing it most likely dates to AD 776-899—this confirms the skull was Anglo-Saxon and not associated with the other archaeological features at the site.

Source: Antiquity, an archaeology journal published in partnership with Cambridge University Press (CUP).

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel